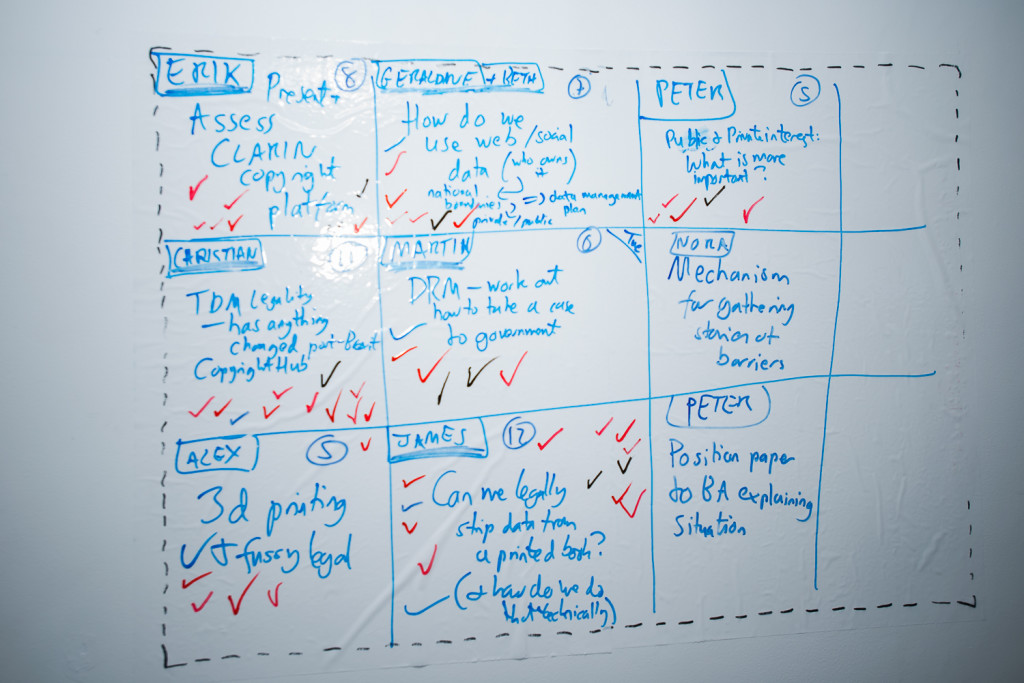

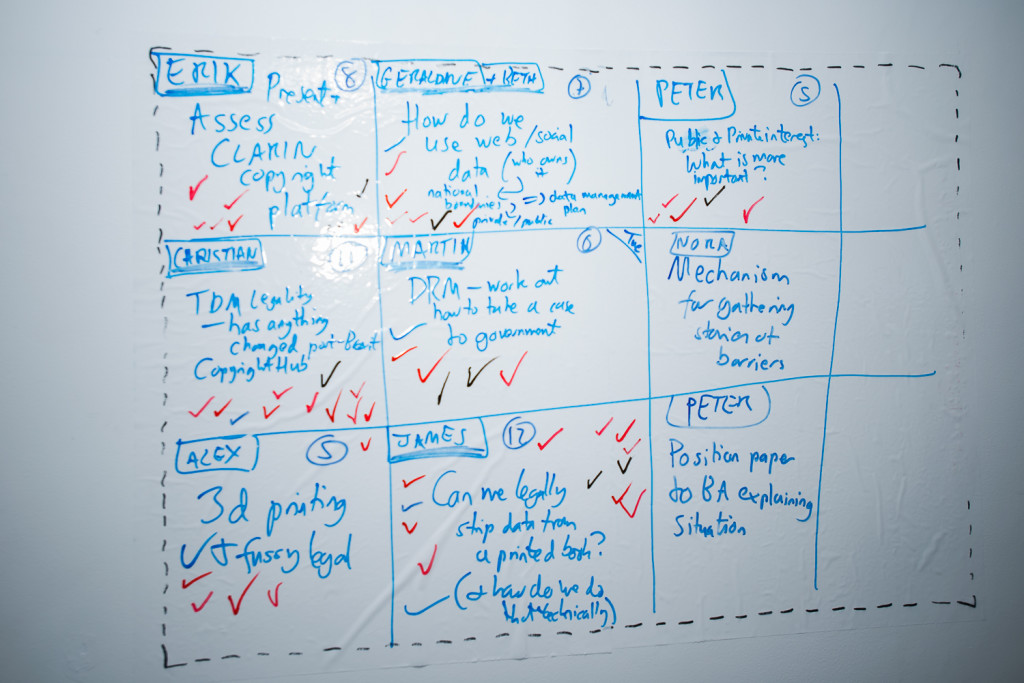

Earlier this month I had the pleasure of hosting the second annual This and THATCamp Sussex Humanities Lab: an unconference event on the THATCamp (The Humanities and Technology Camp) model. A diverse group of people from humanities, library, archives, and law backgrounds attended to work on the theme ‘Rules, Rights, Resistance’ and a prominent part of our work together was around what – legally, ethically, morally – is possible when text and data mining (both in the UK and in other legal jurisdictions).

The event was lively, energetic, and productive. In this post, I want to focus on a session I proposed: ‘Capturing Data Locked Away in History Books‘. My motivation for this session was framed by a simple problem: there is lots of tabular data locked away in history books but what can we do to get it out? And so there are two aspects to this problem: what is allowed and what is technologically possible.

On the legal side, we turned – as we had for much of the event – to the UK Text and Data Mining Exception (2014) (see section 29A or this guidance for more info). From this we inferred that the following was relevant to what we were trying to achieve:

- Printed books are ‘works’ and those works are subject to copyright (even if they are out of print).

- We have ‘lawful access’ to those books if we buy them or can get them from a library.

- When we have lawful access to books we can text and data mine those books.

- That text and data mining can only be on a non-commercial basis.

- Text and data mining in the context of research at a university probably constitutes non-commercial research in most cases (unless of course we are making lots of money from it!).

- We cannot share the data we are text and data mining (either with a research group or with peer reviewers).

- We can share outputs from the text and data mining that are facts (so, something like word counts).

- We can write about what we have done.

During the day, we were introduced to the excellent ‘Legal Information Platform‘ developed by CLARIN and aimed at Digital Humanities researchers. This research has lots of excellent advice on text and data mining and will be updated as the law develops (which it will!).

Shortly after the event, I also found the Jisc guide The text and data mining copyright exception: benefits and implications for UK higher education. This is not only another useful resource (if UK specific) but also one that contradicts our understanding during the camp about the ability to share the data we are text and data mining. John Kelly – the author of the guide – writes:

NOTE: Within the context of research projects involving groups of people across institutions, sharing access to a lawfully mined copy is likely to be acceptable as long as each member of the group has lawful access to original content being mined.

Recommendation: Any TDM undertaken by research groups should ensure that all individuals have lawful access to the original work either through their own institution or via registration at the institution where the mining takes place.)

The point is then, read the various guides, make an estimation of the risks involved, and seek legal advice if you are unsure. In many cases your university library will be able to help.

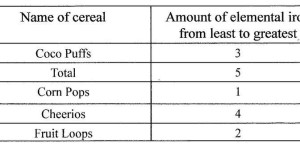

On the technology side, we started by taking photographs (using a nice camera and a smartphone) of pages in history books that contained tables. We then tested a range of Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software to see if it was able to recognise tables and the characters within those tables. We looked at Tesseract (open source OCR software), ABBYY Finereader, Google Drive, and various conversion websites (including Convertio, the Google Vision API, Awesome OCR, and Tabular. We also observed that – for those with member access – the EU-funded IMPACT project contains a demonstrator platform for testing various OCR software/services against various types of textual data.

What we found was that, broadly speaking, online conversion tools are poor at converting tables in history books into data. The exception was Convertio which – we think – was using layout recognition packages for Tesseract to output surprisingly accurate representations of the data tables. On Tesseract, we found that the core installation (for example, via Docker here or here) doesn’t come with layout recognition packages installed (which you need for any non-linear text) and that it is isn’t good at handling warped images. This means that, where possible, scanning on a flatbed – which not everyone has – is better than on a phone or a camera. ABBYY Finereader 12.1.6 – a commercial package (now up to version 14) – turned out to be the winner, confirming similar findings reported by Katrina Navickas reported during her work on the Political Meetings Mapper. Although Finereader didn’t get all the values in the tables right, we put that down to poor quality images (it was only tested by us using mobile phone pictures). What Finereader did very well was recognise a) that there was a table on the page and b) the layout of that table, and output that as structured html or xml (export formats Tesseract can handle as well).

Together, we figured out what to do, what we think the law allowed us to do, and which tools offered the greatest potential for further work. Lots of tabular data is still locked up in history books and – in the UK context at least – the Text and Data Mining Exception doesn’t appear to offer the prospect of getting that data out, combining that data, and sharing that data. But I certainly have a better sense of the legal and technological landscape in which I work than I did going in. Which is the point of hosting a THATCamp.